The Sledgehammer Ladder Match, the Ghost of 2003, and WWE’s Fear of Letting Go

There are bad wrestling matches, and then there are explanatory wrestling matches.

Triple H vs. Kevin Nash at TLC 2011 belongs firmly in the second category. It is not merely remembered because it was slow, awkward, or ill-conceived. It is remembered because it exposed something fundamental about WWE in 2011: a company standing at the edge of change, staring into it, and stepping backwards.

On paper, the match had everything WWE traditionally trusted. Big names. History. A gimmick. A violent promise. In practice, it became one of the clearest case studies in how nostalgia, ego, and narrative panic can suffocate momentum rather than stabilise it.

This was not just a match. It was a confession.

The Match That Didn’t Know What It Wanted to Be

At WWE TLC: Tables, Ladders & Chairs 2011, Triple H and Kevin Nash competed in what was officially called a Sledgehammer Ladder Match. The premise was already self-defeating.

A sledgehammer was suspended above the ring. A ladder was required to retrieve it. Once retrieved, the sledgehammer could be legally used. But the match could not be won by climbing the ladder. Victory could only come via pinfall or submission.

In other words, the ladder did not represent an ending. It represented paperwork.

This mattered because ladders in WWE mythology are not neutral objects. They are symbols of escalation. Finality. Risk. When you strip that meaning away, you are left with a prop that creates movement without purpose.

And purpose was exactly what this feud lacked.

How the Summer of Punk Lost Control of the Narrative

To understand why Triple H vs. Kevin Nash even existed in 2011, you have to revisit the moment WWE almost reinvented itself and then panicked.

The Summer of Punk cracked the company open. CM Punk questioned authority, mocked management, and positioned himself as both insider and insurgent. WWE leaned into it just enough to feel dangerous.

Then Kevin Nash returned.

At SummerSlam 2011, Nash attacked Punk immediately after Punk defeated John Cena to win the WWE Championship. Alberto Del Rio cashed in Money in the Bank. Punk’s victory, which should have felt era-defining, became transitional.

The explanation that followed was infamous.

Nash claimed Triple H, acting as on-screen COO, had texted him instructions to “stick the winner.” Then came the reveal that Nash had stolen Triple H’s phone and texted himself, framing his former friend in order to force relevance and leverage.

The storyline was absurd, but more importantly, it shifted gravity. Punk went from revolutionary to accessory. Authority drama replaced rebellion. Corporate intrigue replaced ideological conflict.

When Nash was ruled medically unfit to face Punk at Night of Champions, WWE made a decision that permanently altered perception: Triple H inserted himself and defeated Punk.

From that moment on, the Summer of Punk was no longer Punk’s story. It was WWE’s story about itself.

Triple H, the Character, Could Not Let the Moment Pass

The key issue was not Kevin Nash’s return. It was Triple H’s positioning.

As on-screen COO, Triple H was meant to represent a new type of authority. Less cartoonish. More corporate. A bridge between eras. Instead, the character reverted under pressure.

When Punk challenged legitimacy, Triple H responded by becoming the final boss again.

The match at Night of Champions wasn’t just controversial because Punk lost. It was controversial because it signalled that, when push came to shove, WWE still trusted Triple H the wrestler more than the story he was supposed to be stewarding.

That decision demanded justification. And justification required a feud.

Enter Nash.

The Feud Nobody Asked For, Extended Beyond Necessity

Kevin Nash’s involvement did not end with Night of Champions. He interfered repeatedly. Cost matches. Appeared without momentum or menace. The storyline became recursive: Nash interferes, explanations follow, nothing resolves.

In October 2011, WWE escalated with the “broken neck” angle. Nash attacked Triple H with a sledgehammer while Triple H was strapped to a stretcher. It was sold as a career-threatening injury.

This should have been a write-off. A way to remove Triple H from television and refocus attention.

Instead, it became justification for TLC.

The sledgehammer wasn’t a stipulation. It was a metaphor WWE refused to drop.

TLC 2011: A Match Built to Hide, Not Reveal

Kevin Nash was 52 years old. His knees were shot. His movement was limited. Everyone involved knew this.

So the match was constructed as smoke and mirrors. Ladders slowed pace. Tables provided spectacle without repetition. Triple H did the majority of movement and positioning.

One key sequence saw Triple H trap Nash’s legs with a ladder and apply a Figure Four through the rungs, explicitly referencing Nash’s quad history. This was arguably the smartest piece of storytelling in the match, because it acknowledged reality instead of pretending otherwise.

But it also highlighted the problem. When your best psychology revolves around why someone can’t move, you’re already losing.

The table bump, where Nash fell from a ladder through a table on the outside, was the match’s singular visual. It was treated as climactic because the match had nowhere else to go.

From there, the end was inevitable.

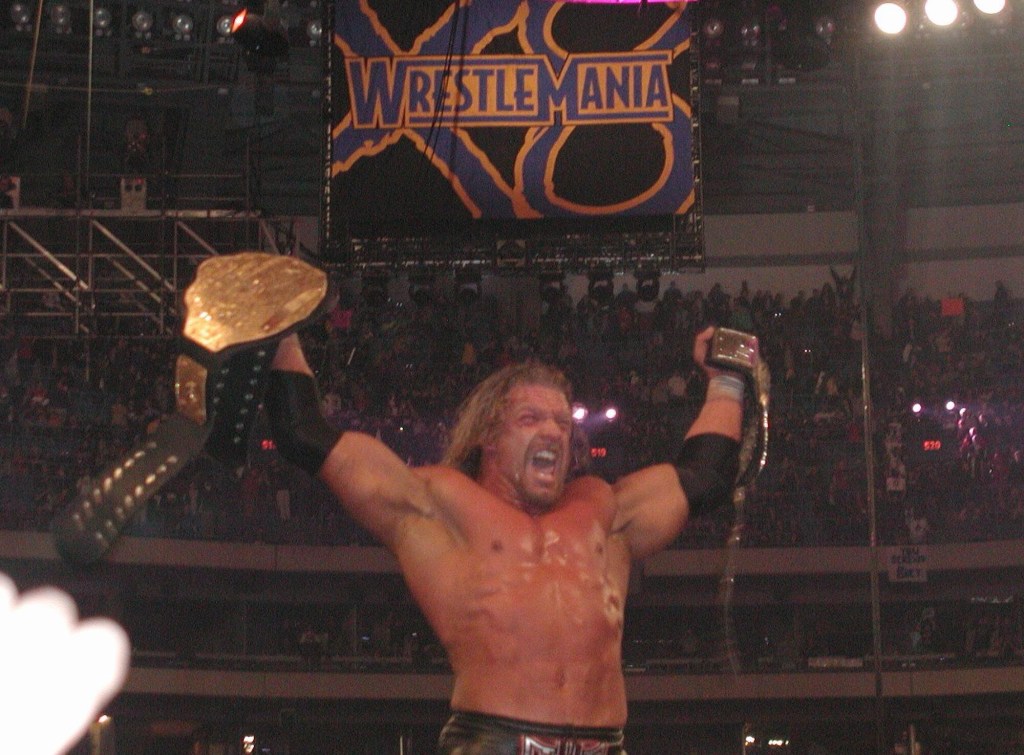

The Finish and the Kliq Callback That Defined Everything

When Triple H retrieved the sledgehammer, Nash crawled toward him and flashed the Kliq hand signal. Too Sweet. A real-life plea. Memory weaponised.

Triple H responded with the DX crotch chop. Sledgehammer shot. Pedigree. Pinfall.

On one level, it was clean storytelling. Friendship rejected. Past severed. Closure achieved.

On another, it was WWE once again choosing symbolism for insiders over meaning for the audience.

The moment mattered to Triple H and Kevin Nash. It did not matter to the larger story WWE was supposed to be telling.

Why the Match Was Rejected So Completely

Criticism of this match was not about star ratings alone. It was about opportunity cost.

First, the stipulation. Ladder matches without ladder endings violate audience expectations. It felt like WWE was using a recognisable brand to sell a match that didn’t belong there.

Second, the pacing. This was not compellingly brutal. It was slow in a draining way. A slog, not a struggle. Ladders, traditionally symbols of chaos and athleticism, became anchors.

Third, the context. This match existed because WWE did not trust the present enough to let it stand without intervention from the past.

Dave Meltzer’s famously low rating became shorthand, but the deeper issue was that this match felt defensive. Like WWE protecting itself from the future it had accidentally unleashed.

The 2003 Parallel: History Repeating with Less Purpose

This was not the first time Triple H vs. Kevin Nash had failed.

Their 2003 Hell in a Cell match at Bad Blood exists as a near-perfect parallel. That feud also revolved around friendship, betrayal, and Triple H asserting dominance during the “Reign of Terror.”

The difference was context. In 2003, the feud was at least anchored to the World Heavyweight Championship. Stakes existed, even if audiences rejected the outcome.

That match also relied heavily on Mick Foley as a buffer. Foley bled. Foley took insane bumps. Foley carried urgency that the competitors could not. In retrospect, the unintentional comedy of Foley popping back up while the wrestlers lay motionless only underlined the problem.

By 2011, even that safety net was gone.

No title. No Foley. Just two men repeating a dynamic that had already been rejected eight years earlier.

What This Match Ultimately Represents

Triple H vs. Kevin Nash at TLC 2011 is remembered because it crystallised WWE’s greatest fear at the time: losing control of the narrative.

CM Punk represented uncertainty. The audience embraced it. WWE responded by reasserting hierarchy, authority, and familiarity.

This match was not about ending a rivalry. It was about WWE reassuring itself that the old order still mattered.

In doing so, it sacrificed momentum, clarity, and trust.

Final Verdict: A Match That Meant More to the Company Than the Audience

Kevin Nash called it his last match. And in that sense, it served a purpose.

But for WWE, it stands as a warning.

You cannot climb backwards into relevance. You cannot use ladders to reach the past. And you cannot suspend a sledgehammer above the ring and expect it to fix structural problems.

Triple H won. Nash retired. WWE moved on.

But for one night in December 2011, the company told on itself. And the echo of that confession still hangs in the rafters.