Edinburgh is a city haunted by extensions. Extend the festivals, extend the tram line, extend the skyline with soulless glass blocks, and now extend the dream — Hibernian FC trying to push themselves into the group stage of a UEFA competition for the first time in their 150-year history.

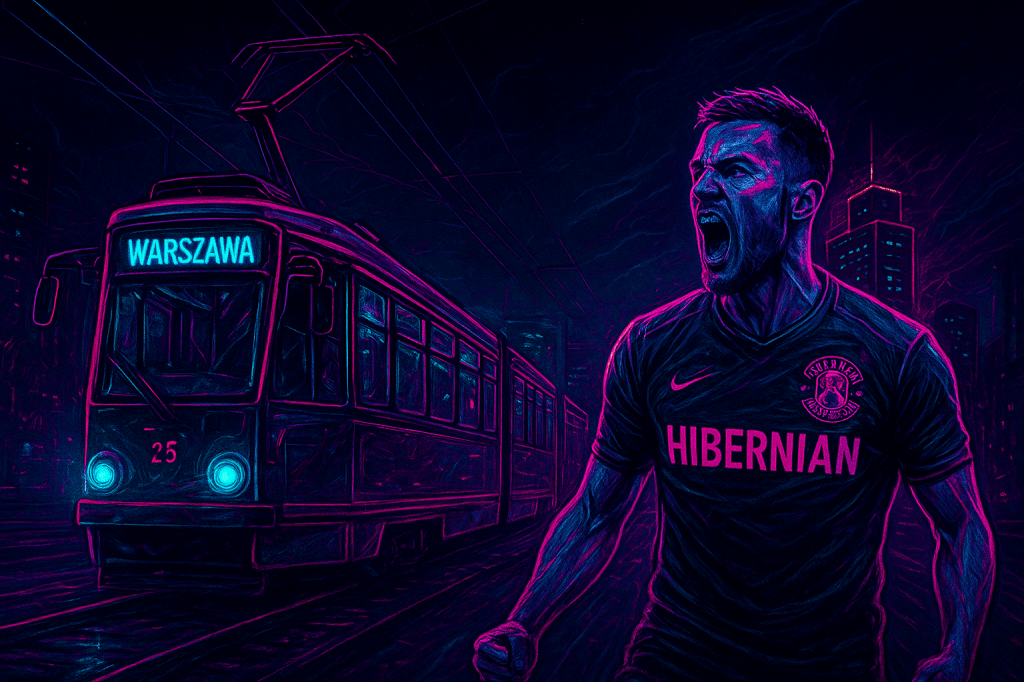

It sounds small on paper — a play-off for the third-tier European tournament. But for Hibs, it’s seismic. This is the point where heritage, frustration, and longing collide with reality. Thursday night in Warsaw will decide whether David Gray’s squad is ready to write history, or whether the tram buffers slam down once again and the ride is over.

The First Leg: Edinburgh Hesitation, Warsaw Ruthlessness

Easter Road staged Act One, and it followed a script Hibs fans know too well. Early promise, missed chances, and a gut punch courtesy of VAR.

The penalty — Rocky Bushiri punished for being in the way of a football while having an arm attached to his body — was the kind of decision that feels baked into European nights for Scottish sides. Bobby Madden called it “an absolute shambles,” and the anger lingered. But more frustrating than referees was Hibs themselves.

Time and again they carved Legia open. Time and again the finish was scuffed, delayed, or sprayed into the night sky. At this level, you take those chances or you don’t survive. And yet, somehow, a late Josh Mulligan strike flickered life back into the tie. “A big goal,” said David Gray. More than that — it was oxygen. A ticket to Warsaw with hope still in the luggage.

Warsaw’s Cauldron vs Edinburgh’s Unfinished Business

The second leg shifts to Stadion Wojska Polskiego, a place that doesn’t forgive hesitation. Legia fans don’t do half-measures — this is a club where tifos are theatre and flares are punctuation. Their roar is not polite but suffocating.

For Hibs, walking into that atmosphere is like arriving in a city where the tram system actually works. Warsaw’s network was flattened during the war, rebuilt from scratch, then expanded through the 50s and 60s to carry workers to the grey sprawl of Soviet housing blocks and industrial plants. Even when politics tried to kill it off — buses instead of trams, oil imports over coal — it never fully died. After 1989, the city ignored it for a while, starved it of investment, but then the renaissance came: modern rolling stock, intelligent traffic systems, and entire new lines stretching into Tarchomin and Wilanów. Warsaw’s trams are resilient. They break, they rebuild, they extend.

Can Hibs say the same? Or are they more like Edinburgh’s tram scheme: delayed, derided, and perpetually asking supporters to trust in a promise that never quite arrives?

Gray’s Gambit: Not Mission Impossible, But Mission Clinical

David Gray has been clear: this is “not Mission Impossible.” He points to the spirit shown in Belgrade, the resilience in Denmark, the fact that Hibs went toe-to-toe with a side who reached last year’s Conference League quarter-finals. He’s right.

But optimism won’t cut through the Warsaw night. Only ruthless precision will. Gray has drilled it into his players: two chances must mean two goals. There’s no safety net. The postponement of their domestic fixture against Falkirk has bought them preparation time, tactical analysis, fresh legs. Now they must use it.

The spine of the side — Boyle, Obita, Hoilett — speak with belief. “Why can’t we go to Poland and win?” asks Obita. Boyle insists Hibs can break Legia down with balls into the box. Hoilett talks about proving the club’s evolution. Yet all of that hangs on the one question Hibs haven’t answered in Europe: can they be killers, not nearly-men?

The Gambian Factor: Manneh Knows Warsaw

One man who might matter more than expected is Alasana Manneh. The Gambian midfielder, a quiet summer signing, has seen Polish football up close before. During his time at Górnik Zabrze, he learned how brutal, direct, and unforgiving the Ekstraklasa can be. It isn’t just physical — it’s tactical, disciplined, streetwise.

Manneh’s experience could be gold in a midfield where Hibs often lack bite. He knows the Polish rhythm: the way teams press, the way referees interpret contact, the way games tilt towards chaos before snapping back into regimented control. If Gray throws him in, Manneh could be the one who brings calm when Warsaw turns into bedlam.

Legia’s Pedigree: A Club That Lives for Europe

For all of Hibs’ hunger, Legia’s history dwarfs theirs. This is Poland’s giant, a club that reached the European Cup semi-finals in 1970, that has played in 55 UEFA competitions, that has stood on stages Scottish clubs rarely dream of.

Yes, they’ve been chaotic — the infamous 2014 forfeit against Celtic after fielding an ineligible player still stings, as does their 1986 away-goals heartbreak against Inter Milan. But these scars are part of the myth. Legia’s culture is built around Europe: the battles, the atmospheres, the sense that their rightful stage isn’t domestic but continental.

Last season, they reached the Conference League quarter-finals, only falling to eventual winners Chelsea. This isn’t a club dipping its toe in; this is a side used to the deep waters.

Warsaw’s Present Tense: Flux and Fire

Yet Legia are not invincible. They lead 2-1, but their first-leg wastefulness kept Hibs alive. Transfers have stripped the squad — Ryoya Morishita gone to Blackburn, Jan Ziolkowski bound for Roma. It feels like a sell-off, a revolution too fast for stability.

New faces like Ermal Krasniqi and Damian Szymański are promising, but they’re untested in this furnace. Coach Edward Iordănescu insists 99% of his squad is ready, but even he admits Hibs are dangerous in transition, aggressive in set-pieces, capable of hitting hard if ignored.

Warsaw may have trams that run to time now, but Legia’s squad feels more like the 1990s version: patched-up, shifting, and occasionally prone to breaking down.

This tie isn’t just a football match; it’s a clash of civic psyches. Edinburgh, forever hesitant, building trams at a snail’s pace and apologising for ambition. Warsaw, rebuilt from rubble, laying tracks to the future even when politics and poverty said no.

It’s not Mission Impossible. But it is Mission Clinical.